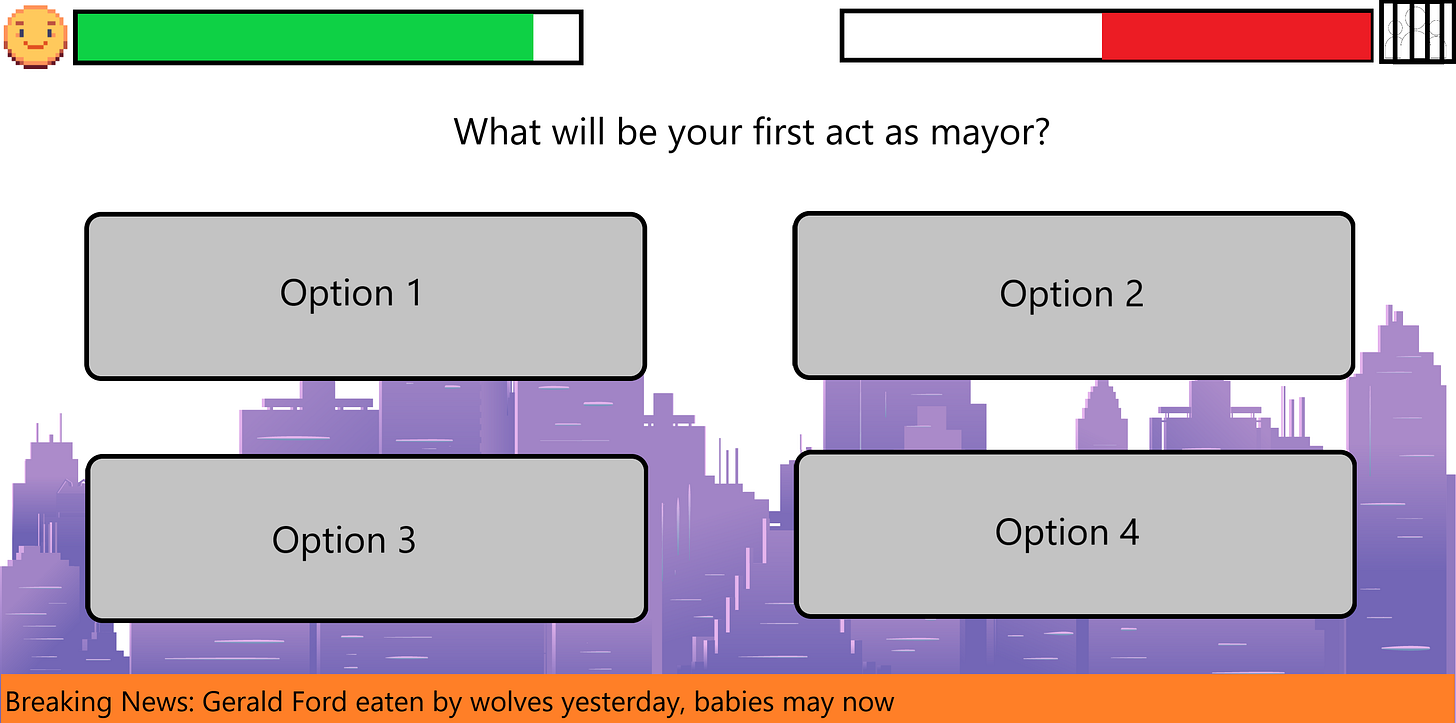

Before I get into this new post, I have two announcements! The first is a project I’ve been slowly working on. It’s a game I’m calling Prison Abolition Simulator. If you’re at all interested, you can follow the progress on my Itch profile. I’ll post more frequent updates over there, and only use this blog for major progress announcements. Here’s a quick mock-up I did in Paint:

The second is a bookshop.org affiliate profile. As I’ve written previously about the harms of Amazon and other corporate monopolies on the publishing industry, and a goal of mine is to present not just problems, but solutions, Bookshop is one solution to the Amazon problem. I learned about it recently through this Wired article. The gist of it is that it’s a platform that allows independent bookstores to have an online presence where through the collection of so many stores, they have more negotiating power with printers/publishers. The website handles basically everything (stores don’t even need to keep a stock of the books sold through the website), and the stores get a percentage of the proceeds from each sale through their page and can also participate in a profit-sharing model. The goal of the founder is to support local bookstores and keep them from succumbing to a monopolistic market while also providing readers with a convenient platform to find whatever they’re looking for. Over the next few weeks I will be updating my past posts with links to books so that those links redirect to my shop page. If you purchase a book through that link, I will receive a small commission (and none of your money will go to Amazon), but I also highly encourage you to find a local book store in your area and purchase through their page as they will receive the proceeds!

I’ll likely keep jumping around to different topics as I read random interesting books, but there will be a running theme of critique of the U.S. criminal justice system, or to be as accurate as possible, the carceral system or punishment bureaucracy. In Ben Austen’s excellent book Correction: Parole, Prison, and the Possibility of Change, he gives a brief overview of the changing perception and intention behind prisons in the U.S. as they were reformed from places of punishment to “correctional facilities”. This change was due to a huge push by reformers to rethink the point of prison from a place to lock people away to a place to rehabilitate people so they are able to return to society (and up to 95% of prisoners are eventually released in the U.S.). Additionally, each year 610,000 people are released from state and federal prisons across the U.S. However, over time those reforms fizzled out in favor of “tough on crime” policies, whose effects end up being tough on society. While other countries like Finland were able to completely overhaul the way they deal with crime and create a truly rehabilitative prison system, the U.S. system became “correctional” in name only.

Austen provides a compassionate account of several men who were given extensive sentences (often when they were just teenagers), and faced massive difficulties trying to convince parole boards to grant them parole. He makes a strong case that parole board decisions are arbitrary. They depend on the mood of the parole board members that day, the political climate, and random events. Even decades later, parole boards will reread the official court description of the crime in grisly detail before taking into consideration the actual behavior and actions of the person since their crime. Unfortunately, because U.S. prisons are not designed to rehabilitate people and prepare them for return to society, inmates are subject to a huge number of arbitrary rules for which they can receive a citation if they break them. These citations are then used by the parole boards to show that they don’t “respect authority” and aren’t ready to be released, even though guards have huge leeway in enforcing the rules or not, and will look for any reason to cite an inmate they don’t like.

The men Austen interviewed took classes, created mentorship programs, and joined debate teams. They prepared a debate for state delegates and made a strong case for the expansion of parole (which had been curtailed for new arrests, with only inmates convicted in the 70s and 80s grandfathered in to qualify for parole). This elimination of parole is part of the “tough on crime” mindset which criminalizes people of color and then treats them as irredeemable. It is a hateful mindset, and completely detached from reality. It insists that people are the worst thing they have ever done and cannot change, but of course the proponents of “tough on crime” policies favor mitigating circumstances whenever they commit crimes. Those eligible for parole often go to extraordinary lengths to improve themselves while in the confines of a system that seeks not to support them, but to make them miserable, in the belief that the condition of the prison itself should be a punishment. However, once they are finally released, many return to their families and communities and attempt to live a normal life, but are confronted with punishment for the rest of their lives in the form of hiring restrictions and general discrimination.

Correction delves deep into the U.S. punishment bureaucracy and highlights the many flaws of a system focused almost entirely on retribution. The stories of several men cross with each other and with evidence of broader trends in the criminal justice system. Overall, the book proves the point that there is always a possibility of change. By comparing U.S. institutions to those of other countries, Austen shows a better world is possible, and we already know what to do to make it happen. I’ve described some successful reforms in my previous posts, but there is much more work to be done. Expanding parole and providing more services and opportunities for incarcerated people to learn and grow is one step toward healthier communities and away from the criminogenic effects of the U.S. punishment bureaucracy.