The Long History of Class in the US

A Review of White Trash

This post is somewhat a continuation of my previous post, a review of Caste. As I mentioned in that review, the one part I felt that the book did not do as well as it could was in connecting race and class. Before I get into my thoughts on White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America (store link), I think I’m going to continue adding a few interesting articles or readings I’ve done at the start of each post.

To add to the massive pile of “corporations committing human rights abuses”, the Guardian reported on June 11th that Chiquita was ordered to pay $38 million to families of people killed by the far-right militia/terrorist group that they funded to prevent left-wing groups from taking the land they were exploiting and redistributing it back to people who needed it to survive. I hope to write up a full-length post in the future on the history of U.S. corporate influence in Latin America and how many lives have been lost because of it. For now, this ruling is a step in the right direction and we can only hope that it is not overturned on appeal. In an example of the depravity of the wealthy:

A spokesperson for Chiquita said the company would appeal the ruling, adding in a statement: “The situation in Colombia was tragic for so many, including those directly affected by the violence there, and our thoughts remain with them and their families. However, that does not change our belief that there is no legal basis for these claims. While we are disappointed by the decision, we remain confident that our legal position will ultimately prevail.”

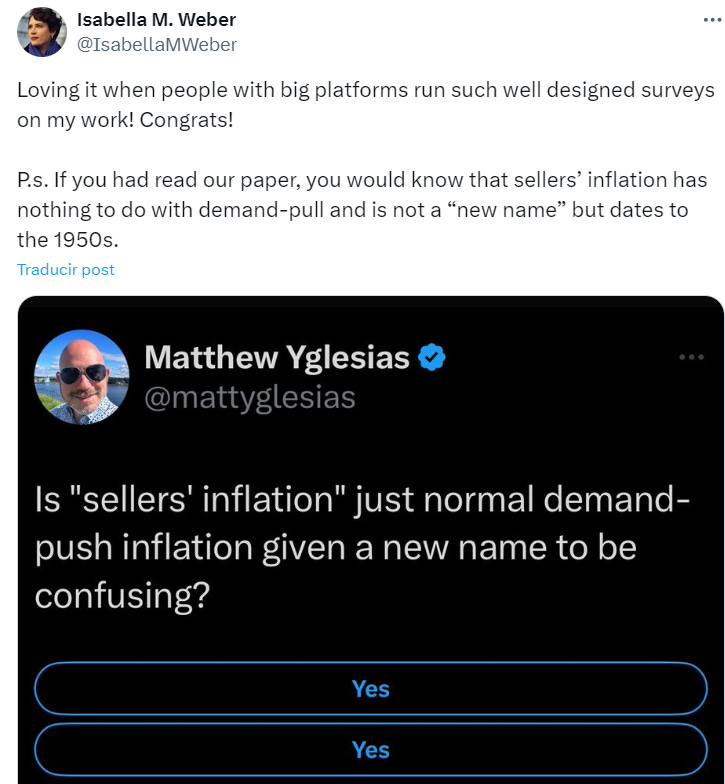

In anti-trust news, Hal Singer, economics professor at the University of Utah who consistently writes smart analysis on labor issues and how neoliberal economists completely ignore power dynamics (and any empirical evidence that contradicts their claims), wrote a good primer on anti-trust law and recent changes in policy. There’s an excellent paper in the George Mason Law review that I wrote about a while back that goes into even more detail if this primer piques your interest. This is in response to a piece by Matt Yglesias, a pundit who is paid to write his very first thoughts about any topic he comes across. After the brief overview, Singer concludes with:

Presumably Yglesias and his neoliberal clan have access to Google Search, Lina Khan’s Twitter handle, or the Antitrust Division’s press releases. It only takes a few keystrokes to learn of countless enforcement actions brought on behalf of consumers. Although this view is a bit jaded, one interpretation is that this crowd, epitomized by the Wall Street Journal editorial board and its 99 hit pieces against Chair Khan, uses the phrase “consumer welfare” as code for lax enforcement of antitrust law. In other words, what really upsets neoliberals (and libertarians) is not the abandonment of consumers, but instead any enforcement of antitrust law, particularly when it (1) deprives monopolists from expanding their monopolies to the betterment of their investors or (2) steers profits away from employers towards workers. In my darkest moments, I suspect that some target of an FTC or DOJ investigation funds neoliberal columnists and journals—looking at you, The Economist—to cook up consumer-welfare-based theories of how the agencies are doing it wrong. All such musings should be ignored, as the antitrust hipsters are alright.

Finally, I’m a huge fan of Orwell and I had just read an essay of his on the complexity of his patriotic feelings right before reading Hamilton Nolan’s essay against nationalism. Both are worth reading, and I especially enjoy Orwell’s ability to work through his thoughts and bring the truth out whether that truth fits within a neat narrative or not.

Now onto the book review. White Trash by Nancy Isenberg, a historian of the U.S. and Professor of History at Louisiana State University, looks at U.S. history from a very different angle than Caste. I went into the book expecting it to focus more on the linguistic history on how poor white people have been treated throughout U.S. history, but it was a much deeper and more detailed account of how class has shaped our society since its founding. One of the founding myths of U.S. society has been that it is classless, or at least that if anyone works hard enough they can advance economically and break through the porous class barriers. This is laughable with even a little knowledge of U.S. history, but having gone through 12 years of public education here, it’s completely understandable to me how so many people believe this.

Many studies have found that it’s harder to achieve the “American Dream” in the U.S than in many other developed countries (see this TED talk from 2016). And in fact, a strong social safety net is a key factor in moving from a low economic class to a higher one. The difficulty gaining wealth is not due to a lack of hard work on the part of the poor, but rather to systemic conditions intended to entrench the class system that has existed since our founding.

I have come to the conclusion that far too often in the U.S. we are concerned more with appearance or aesthetics than with concrete conditions. As detailed by Isenberg, the myth of classlessness in the U.S. seems to have originated in the lack of immediate deference/respect shown to the aristocracy in the U.S. versus European nations in the late 18th century. But this has very little to do with the actual existence of a class-stratified society. Much like Caste, White Trash uses primary sources and the writings of influential people to highlight how class has been embedded in U.S. institutions. There is a distinct interplay between class and race which comes up several times in the book. Mainly, it seems that race has been a tool weaponized by the wealthy to divide the working class.

The most interesting part of the book to me was the description of the charter documents of several early American colonies, and specifically John Locke’s ideology and influence in the formation of new colonial governments in the U.S. Locke, whose enlightenment philosophy was foundational to colonialism, the extractive mindset, and the development of capitalism, was a founding member and third-largest shareholder of the Royal African Company. This company held a monopoly over the British slave trade. Previously I wrote a bit about how I like a lot of the ideas of classical liberalism, but vehemently disagree with the conclusions/actions taken because of this philosophy. This is a continuation of this thought and another topic for a deeper dive in the future. Locke helped to write the Fundamental Constitution of Carolina, which established an aristocratic social order and in which he claimed that all free men are complete owners of their slaves. He was also instrumental in creating and disseminating the idea of “improvement” of land which was used by colonizers to take land from Native Americans. The basic idea being that white Europeans would make much better use of the land and that ownership should be determined not by who was living on the land, but by who would be able to extract the most wealth/resources out of the land. This justification was foundational to the genocide of Native Americans.

Throughout U.S. history, the ruling aristocracy has created different epithets to indicate that the poor are lesser human beings. I believe that the promise of equality in the Declaration of Independence is a great rhetorical tool to advance a classless system, but as shown by comparisons with other countries, we have a long way to go to make the “American Dream” accessible to all. This would require a commitment not to aesthetic changes, but concrete changes to the working and living conditions of all U.S. citizens as well as policy changes I’ve detailed in some of my previous writing. The good thing is, a better understanding of our history reveals that all of our social systems are based on choices that people in the past made, and can be unmade by people today. We just need to get involved in local organizations, political groups, labor unions, or volunteer organizations and push for the values of community and solidarity to actually be implemented in our policies.