Capitalism Is the Cause of, Not Solution to Poverty

According to Research by Jason Hickel and Dylan Sullivan

Mini Review

Today’s mini review is of a book that deserves a full-length review once I have time to get a physical copy and re-read it. Vincent Schiraldi’s Mass Supervision: Probation, Parole, and the Illusion of Safety and Freedom makes an airtight case that probation and parole should be done away with over the next few years. To paraphrase the author, this over 100 year old experiment has proven to cause more harm than good. With so many onerous conditions of parole, not only does it feed mass incarceration, it actually correlates with more crime being committed. This is in much the same way that prison can cause more crime by taking people away from community supports, taking their jobs, separating families, and degrading the very fabric of whole neighborhoods. One interesting fact from the book is that when required check-ins with parole officers were replaced with a computerized system whereby clients answered the same questions on a digital form instead of with their parole officer, they were actually less likely to reoffend.

If you're not yet ready to abolish parole, Schiraldi lays out a solid plan that could lead to its abolition over many years, but with time to carefully study outcomes and make adjustments as you go (as all good policy should be designed). This involves especially focusing on community support and creating opportunities for people both before, after, and as an alternative to incarceration. With more deeply connected neighborhoods that provide job opportunities, and economic support to people involved in the criminal justice system, people are able to reintegrate and are less likely to commit crimes in the future. If you’re looking for safety and freedom, prisons and parole offer neither, but they do cost a lot of money, expand state use of force, and make already difficult conditions worse for poor communities. It’s long past time to do away with the myth that prisons exist to enhance public safety. There are many better ways to use the money we dump into prisons and parole each year, but first we must recognize that better things are possible.

Capitalism Is the Cause of, Not Solution to Poverty

That is, according to research published in World Development in January of 2023 by Dylan Sullivan and Jason Hickel. Jason Hickel does a lot of great research and was one of the authors of the paper I wrote about in my very first post on global inequality. He also wrote this great article summarizing the findings of that research. The highlights at the start of this new paper cover the most significant findings:

The common notion that extreme poverty is the “natural” condition of humanity and only declined with the rise of capitalism rests on income data that do not adequately capture access to essential goods.

Data on real wages suggests that, historically, extreme poverty was uncommon and arose primarily during periods of severe social and economic dislocation, particularly under colonialism.

The rise of capitalism from the long 16th century onward is associated with a decline in wages to below subsistence, a deterioration in human stature, and an upturn in premature mortality.

In parts of South Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America, wages and/or height have still not recovered.

Where progress has occurred, significant improvements in human welfare began only around the 20th century. These gains coincide with the rise of anti-colonial and socialist political movements.

To reiterate, human beings across the world broadly had access to livable conditions in which they were able to “support a family of four above the poverty line by working 250 days or 12 months a year, except during periods of severe social dislocation, such as famines, wars, and institutionalized dispossession – particularly under colonialism.” It’s important to point out here that colonialism was a key stage in the rise of capitalism as it fueled the accumulation of capital in the imperial core countries of Europe. The authors find that “the rise of capitalism caused a dramatic deterioration of human welfare” and in some areas of the world human living conditions and well-being still have not recovered to the level they were before those areas were incorporated into the capitalist world system.

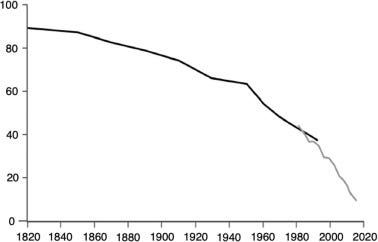

This paper is important as it challenges the broadly espoused narrative that capitalism has led to a continuous reduction in poverty around the world. The authors begin by critiquing the data used to draw these conclusions (for an older, but still worthwhile version of this critique, see this Guardian article). First, they note that a graph used by Steven Pinker (not an economist) in his popular book Enlightenment Now is highly misleading. Ignoring, for a moment, the fact that the World Bank’s definition of extreme poverty requires “extreme calorie and nutrient deficits and an inability to access basic goods”, the graph starts in 1820 and depicts the percent of the world population living in extreme poverty as starting around 90% and declining more rapidly each year until just before 2020 when it has reached its lowest level so far.

This starting point implies that before 1820 poverty would have been even higher, but a review of several historical metrics shows that for most of human history people have not been living in extreme poverty, and in many regions the living conditions of regular laborers were better before the rise of capitalism. That is to say, laborers often had better nutrition and could access more than the necessary food, clothing, and fuel to provide for their families in the 1300s than even in 2010.

In addition to this, the authors provide a strong methodological critique of the World Bank’s method of determining extreme poverty, which now sits at $1.90 per day. This rate is “calculated based on prices across the whole economy, while what matters for the purposes of assessing poverty is the prices of essential goods that are necessary to meet basic needs (such as food, housing, fuel).” As an alternative, other researchers have developed a

“Basic Needs Poverty Line (BNPL) which consistently allows people to consume 2,100 calories per day, 50 g of protein, 34 g of fat, and various vitamins and minerals, all from the cheapest available foods, in addition to some non-food items like clothing, housing, fuel, and lighting. The contents of this subsistence basket are not narrowly defined, but are allowed to change as prices change, so that people may meet these nutrient requirements at the least cost.”

As Hickel and Sullivan note, these methodological differences, with the BNPL attempting to measure what people truly need to cover their basic necessities, and the World Bank Measure which is both far too low and does not consider the goods that people truly need to survive, lead to very different understandings of the world and economic history.

Consider the case of China, for example. According to the $1.90 method, the poverty rate in China fell from 66% in 1990 to 19% in 2005, suggesting capitalist reforms delivered dramatic improvements (World Bank 2021). However, if we instead measure incomes against the BNPL, we find poverty increased during this period, from 0.2% in 1990 (one of the lowest figures in the world) to 24% in 2005, with a peak of 68% in 1995 (data from Moatsos, 2021).3 This reflects an increase in the relative price of food as China’s socialist provisioning systems were dismantled (Li, 2016).

These revelations continue throughout the paper as it details empirical markers of well-being in Europe, Latin America, Africa, and Asia. In almost all cases the rise of capitalism led to a decline in well-being, including in Europe itself, where, to use Amsterdam as an example, in 1875 the average worker was worse off than in 1400. Conditions generally improved across Western Europe by the mid-20th century, though as discussed in the articles linked in the first paragraph, this was at the expense of the former colonies which in many cases still have not reached their pre-capitalist levels of well-being for workers. It’s also worth noting that in recent history most periods of dramatic decrease in poverty have corresponded to strong labor movements or socialist provisioning, not to capitalist policies.

Upon examining Latin America, “there is no evidence that extreme poverty rates approached 90% in most periods.” This again debunks the assumption of Steven Pinker’s graph that 90% extreme poverty was normal throughout history until the “progress” seen under a capitalist economic system. The BNPL data shows a decrease or stagnant welfare standards for Latin American laborers until a spike in the 1930s-40s followed by a dramatic drop in the 1980s. As the authors note:

Wages started to improve from the 1940s, as labour unions grew rapidly, and populist or left-wing governments assumed power (Rock, 1994, Prashad, 2007, pp. 25-27, 62-74). Over the following decades, these governments created anti-colonial developmentalist institutions (such as the UN Economic Commission for Latin America based in Santiago de Chile), and pursued import-substitution policies aimed at independent industrialization (Klein, 2007, pp. 54–55; Prashad, 2007, pp. 62-74; Chang, 2007). Most countries surpassed their 18th century peak in the 1960s. However, these gains were reversed under the structural adjustment programmes imposed by the World Bank and IMF during the 1980s and 1990s (ibid; Klein, 2007, pp. 156–168; Hickel, 2017, pp. 149-166). In Mexico, the welfare ratio declined from 4.22 in 1982, to 1.01 in 1984. As of the 2000s, Mexico had lower wages than three centuries earlier.

It’s worth pulling out that last sentence for emphasis: “As of the 2000s, Mexico had lower wages than three centuries earlier.”

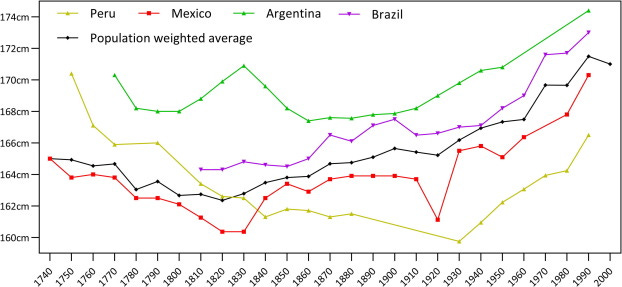

Another facet of human well-being the authors considered for each region was height (pictured above for Latin America). This is useful as an indicator of childhood nutrition levels. While this data for Latin America only goes back to the 1700s, whereas the conquest and subsequent introduction of capitalism to the Western Hemisphere began in 1492, we can see that there was a decline in average height from 1740 onward, with 1820 being a low point for many countries. Considering the narrative of ever-increasing progress due to capitalism promoted by Pinker and others (remember that his graph started in 1820, the low point for Latin America), we see that the progress that has been made is often in relation to the deep deprivation and decline in living conditions first created by capitalism. As of 1990, Peru still had a lower average height than in 1750.

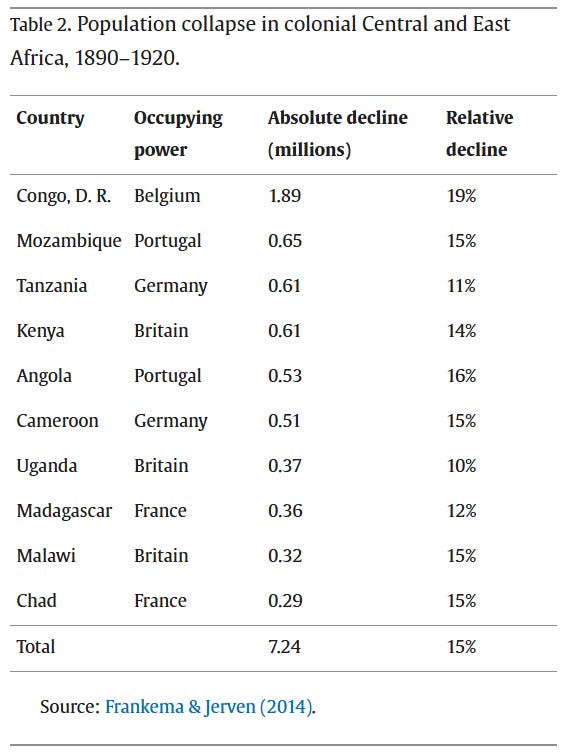

The third main indicator Sullivan and Hickel relied on was data on mortality. In all regions, the introduction of capitalism led to excess mortality and increased frequency of famines. Considering Mauritius, the only African country with 19th century mortality figures, “under British rule, deaths per 1,000 people rose from an average of 28.3 in the 1870s, to 37.5 in the 1900s (Mitchell, 2013). Unless there were anomalies in the rate of registration over time, these figures suggest there were 74,505 excess deaths between 1885 and 1920.” Below is a table of population decline due to capitalist colonization of Africa.

One common defense of capitalism is to point to the massive deaths from famine during The Great Leap Forward in China, the point being that a communist or socialist system must necessarily cause death and be worse than a capitalist one. The authors address this directly in a passage worth quoting extensively:

The health of the Chinese population improved markedly from 1950 to 1980. According to Babiarz et al. (2015, p. 39), Maoist China “experienced the most rapid sustained increase in life expectancy of any population in documented global history,” primarily because the government expanded public health care and education (see also, Dreze & Sen, 1989, pp. 204-225). There was, of course, a mortality crisis during the famine from 1958 to 1961, which was induced by a lack of democracy (Dreze & Sen, 1989, pp. 210-215). But outside of those dark years, China experienced exceptionally rapid gains against mortality, with the death rate dropping to 6 per 1,000 by 1978 (World Bank 2022). For perspective, India and many other low-income capitalist states did not approach this level until the 2010s. As Dreze & Sen (1989, pp. 214-215) point out: “despite the gigantic size of excess mortality in the Chinese famine, the extra mortality in India from regular deprivation in normal times vastly overshadows the former…. [E]very eight years or so more people die in India because of its higher regular death rate than died in China in the gigantic famine of 1958–61.” [emphasis mine]

To reiterate, the regular deprivation due to a capitalist economy which does not guarantee even basic subsistence in India has caused many times more deaths than the famine in China. Make no mistake, just as it is a choice to centralize an economy and try to manage it through the government, it is also a governing choice to leave the provision of basic necessities to private individuals seeking profit. In this case, we see that the choice causes millions of excess deaths per year due to the deprivations inherent in a capitalist economic model.

There are many more arguments to be made about the excess deaths caused by capitalism including the famines in India due to the British colonial extraction, and continued wars and repression around the world which have resulted in the deaths of millions of people by dictators propped up by capitalist nations to maintain their extractive trade regimes. I hope to write more in depth on that in a future post. Suffice it to say, the unquestioned goodness of capitalism in the U.S. and in many developed nations does not hold up to scrutiny. There is plenty of room to debate the best way to organize the provision of goods, both necessary and luxury, but it’s time to move past the assumption that capitalism is the most beneficial economic system to the most people. It’s just not true and starting from that assumption greatly limits our potential to improve living conditions for the people who most need it. Sullivan and Hickel make the case eloquently in their conclusion:

Contrary to claims about extreme poverty being a natural human condition, it is reasonable to assume that human communities are in fact innately capable of producing enough to meet their own basic needs (i.e., for food, clothing, and shelter), with their own labour and with the resources available to them in their environment or through exchange. Barring natural disasters, people will generally succeed in this objective. The main exception is under conditions where people are cut off from land and commons, or where their labour, resources and productive capacities are appropriated by a ruling class or an external imperial power. This explains the prevalence of extreme poverty under capitalism. Capitalism is a highly productive system, but it is also undemocratic: decisions about what to produce and how to use surplus are determined by the few who own and control the means of production (Chomsky, 2013, Albert, 2003, Wood, 1981). For capital, the purpose of production is not primarily to meet human needs, as we might expect in a more democratic system, but rather to extract and accumulate profit.

P.S. - If you like what you read, please share with anyone you think might be interested. If you really like it, I now have a Ko-Fi page set up where you can send me a tip and tell me what post sparked your interest.

Purchase the Book

If you’d like, you can purchase some of the books mentioned in this post from bookshop.org. This is a way to support local bookstores (or me if you use the link below), and avoid the Amazon monopoly.

Here is the link to my store page, with all of my recommendations.

You can also use the store locator and select a local book shop for the profit of your purchase to go to. According to the website:

When you select your local bookstore on the map above and visit their Bookshop.org page, we place a cookie in your browser that identifies you as that store's customer, and the store will get the full profit from all your Bookshop.org purchases (30% of the book's list price).

Really insightful essay, it will be really helpful to share with my coworkers who are more supportive of capitalism.